- Page 1

- Page 2

- Page 3

- Page 4

- Page 5

- Page 6

- Page 7

- Page 8

- Page 9

- Page 10

- Page 11

- Page 12

- Page 13

- Page 14

- Page 15

- Page 16

- Page 17

- Page 18

- Page 19

- Page 20

- Page 21

- Page 22

- Page 23

- Page 24

- Page 25

- Page 26

- Page 27

- Page 28

- Page 29

- Page 30

- Page 31

- Page 32

- Page 33

- Page 34

- Page 35

- Page 36

- Page 37

- Page 38

- Page 39

- Page 40

- Page 41

- Page 42

- Page 43

- Page 44

- Page 45

- Page 46

- Page 47

- Page 48

- Page 49

- Page 50

- Page 51

- Page 52

- Page 53

- Page 54

- Page 55

- Page 56

- Flash version

© UniFlip.com

- Page 2

- Page 3

- Page 4

- Page 5

- Page 6

- Page 7

- Page 8

- Page 9

- Page 10

- Page 11

- Page 12

- Page 13

- Page 14

- Page 15

- Page 16

- Page 17

- Page 18

- Page 19

- Page 20

- Page 21

- Page 22

- Page 23

- Page 24

- Page 25

- Page 26

- Page 27

- Page 28

- Page 29

- Page 30

- Page 31

- Page 32

- Page 33

- Page 34

- Page 35

- Page 36

- Page 37

- Page 38

- Page 39

- Page 40

- Page 41

- Page 42

- Page 43

- Page 44

- Page 45

- Page 46

- Page 47

- Page 48

- Page 49

- Page 50

- Page 51

- Page 52

- Page 53

- Page 54

- Page 55

- Page 56

- Flash version

© UniFlip.com

J A N U A RY • F E B R U A RY 2 0 1 5

A BRIDGE TOO FAR?

continued from page 34

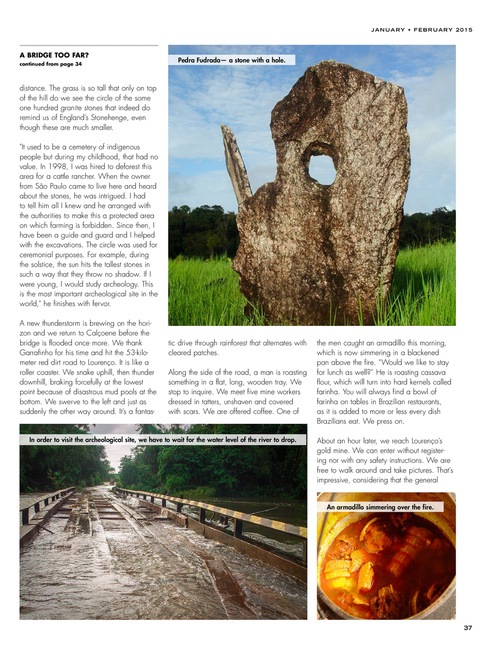

Pedra Fudrada— a stone with a hole.

distance. The grass is so tall that only on top of the hill do we see the circle of the some one hundred granite stones that indeed do remind us of England’s Stonehenge, even though these are much smaller. "It used to be a cemetery of indigenous people but during my childhood, that had no value. In 1998, I was hired to deforest this area for a cattle rancher. When the owner from São Paulo came to live here and heard about the stones, he was intrigued. I had to tell him all I knew and he arranged with the authorities to make this a protected area on which farming is forbidden. Since then, I have been a guide and guard and I helped with the excavations. The circle was used for ceremonial purposes. For example, during the solstice, the sun hits the tallest stones in such a way that they throw no shadow. If I were young, I would study archeology. This is the most important archeological site in the world," he finishes with fervor. A new thunderstorm is brewing on the horizon and we return to Calçoene before the bridge is flooded once more. We thank Garrafinho for his time and hit the 53-kilometer red dirt road to Lourenço. It is like a roller coaster. We snake uphill, then thunder downhill, braking forcefully at the lowest point because of disastrous mud pools at the bottom. We swerve to the left and just as suddenly the other way around. It’s a fantas-

tic drive through rainforest that alternates with cleared patches. Along the side of the road, a man is roasting something in a flat, long, wooden tray. We stop to inquire. We meet five mine workers dressed in tatters, unshaven and covered with scars. We are offered coffee. One of

the men caught an armadillo this morning, which is now simmering in a blackened pan above the fire. “Would we like to stay for lunch as well?” He is roasting cassava flour, which will turn into hard kernels called farinha. You will always find a bowl of farinha on tables in Brazilian restaurants, as it is added to more or less every dish Brazilians eat. We press on. About an hour later, we reach Lourenço’s gold mine. We can enter without registering nor with any safety instructions. We are free to walk around and take pictures. That’s impressive, considering that the general

An armadillo simmering over the fire.

In order to visit the archeological site, we have to wait for the water level of the river to drop.

37